Failed by the System: Navigating

Housing and Eviction in Evanston

“Number 33,” laughed Judge James L. Allegretti, during the November 22 session of the weekly eviction trials at the Cook County Circuit Court Second Municipal District. “I don’t even know their names.”

The depersonalized conduct of eviction court is a trend for tenants across the country. For Thia Dannen, a single mother and two-time evictee who hails from Killeen, Texas, attending eviction court was an overwhelmingly dehumanizing experience.

“They pretty much talk to you like you’re nothing and it's your fault and they're not willing to work with you,” she said. “I’m just glad my kids weren't there.”

Outside the courtroom entrance, a row of seats accommodate the overflow of the 43 renters facing judgement. Here, a tenant frantically sifts through a manila folder of bank statements and complaints before being called to face the judge. In this court, which serves the northern suburbs of Cook County, 55.7% of decisions ended in eviction orders or a judgement against the tenant from 2014 to 2017. Regardless of the outcome, any appearance in court creates a public eviction record.

However, attending eviction court is only one destination on a journey full of numerous hurdles within the housing system that tenants must navigate to mitigate the threat of eviction.

The journey begins with securing housing. In Evanston, the Tenant-Based Rental Assistance (TBRA) program helps unstably housed or homeless families with children in the local school districts find housing. In August, the Evanston Housing and Homelessness Commission approved a $300,000 renewal request for the program, which would allow the city to provide rental and utility aid for 10 families for two years.

However, experts say the need far exceeds what the Commission can supply. 1,880 people are currently on the waitlist for the Housing Authority for Cook County (HACC), which is closed to new applicants.

According to Sarah Flax, Evanston Housing and Grants Division Manager, every waitlist for affordable housing in Evanston is closed. Due to limited waitlist sizes, Flax said she advises tenants to “try to get on all of the potential lists you're interested in because one of them may come through before another.”

Being on a waitlist does not guarantee housing. “Some people have been on a waitlist since probably sometime in 2015 or said they were interested, and still haven't gotten units,” Flax said.

Flax says that the root of the problem lies in funding. “The biggest challenge is simply there aren't the financial resources to help everybody who needs to be helped,” she said. “Nationally we're just underresourced for the housing need and that’s not something that is changing rapidly.”

The City of Evanston creates its housing budget largely based on grant money from the federal government; however, the amount of funds allocated is uncertain. Flax said that these uncertainties not only force the city to plan the budget more conservatively, but they also “make it difficult to be very consistent or effective in deciding how to use resources on an ongoing basis.”

Additionally, the White House budget for fiscal year 2020 projects the termination of the HOME Investment Partnerships Program, the federal grant responsible for appropriating the funds that the Evanston government allocates for programs like TBRA. That would mean $355,216 of financial aid for Evanston residents facing eviction would be lost.

For Randall Leurquin, a data analyst and special projects manager at the Lawyers’ Committee for Better Housing, the lack of national commitment is worrisome, especially considering that there is a shortage of 6,790 units of affordable housing in Evanston.

“I think people are definitely concerned about high rates of evictions, lack of affordable housing,” he said. “If we’re going to have a diverse city, and that’s the goal, we have to have resources for people who aren’t six-figure income earners.”

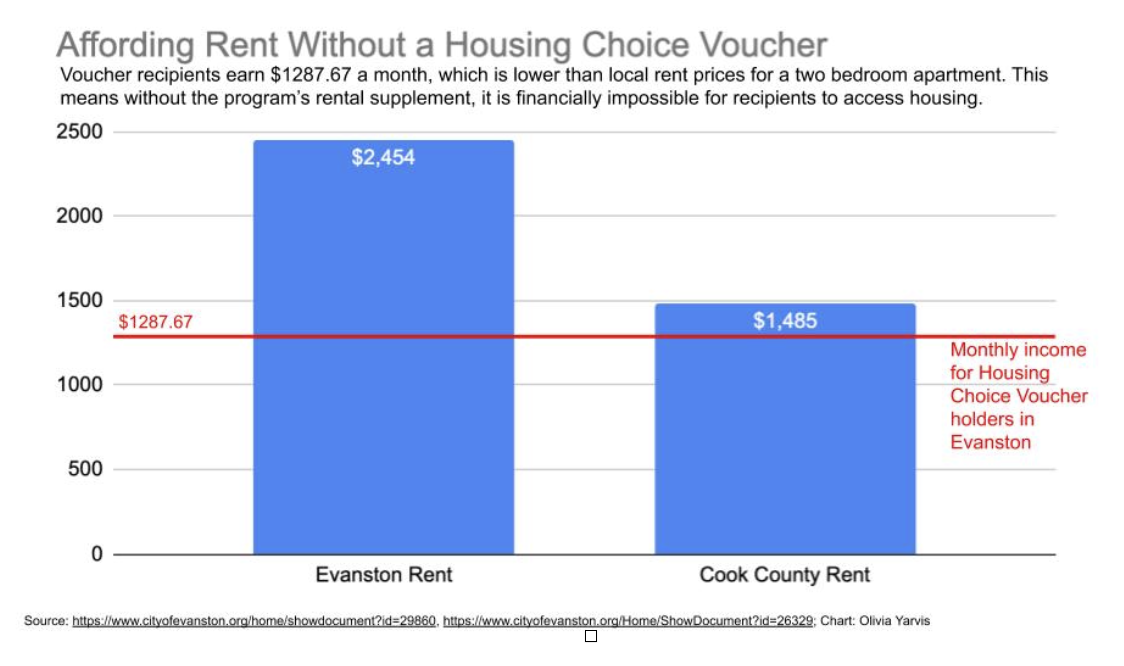

Another system affected by national budget cuts is the Housing Choice Voucher program, a rental payment assistance program that helps connect tenants to low-cost housing. This connection is especially important because voucher holders earn $52,840 less per year than the average Evanston resident.

This is a program that Morris “Dino” Robinson, an Evanston landlord, is no stranger to. Robinson has had three different tenants, two of which were voucher holders. He recalled one experience in which HACC failed to process the necessary paperwork that he and his tenant submitted, which automatically kicked them off of the voucher program.

“I think it's designed to make it as difficult as possible because the goal is to get as many people off their voucher program by cheating them out. That’s what it feels like,” Robinson said. “Cheating them out or making it difficult so that they lapse or lose their voucher. Once they lose their voucher it's extremely hard to get it back, if they can ever get it back.”

However, tenants who lose their voucher are still required to pay either partial or full rent, just without government assistance. When this subsidized aid falls short, whether through lack of funding or inefficient bureaucracy, tenants have to face the unfavorable odds of eviction court.

After navigating these systemic deficiencies, Dannen found that tenants are denied the ability to participate in maintaining their housing stability, or worse, tenants assume the full blame for their circumstances.

“For people who do have evictions, just don’t write us off as lazy people who don’t want to pay their bill, just get to know us and justify our situation first,” she said. “A lot of people, I'm sure, who do have evictions, are good people, and they are willing to pay their bills, if someone is willing to work with them.”